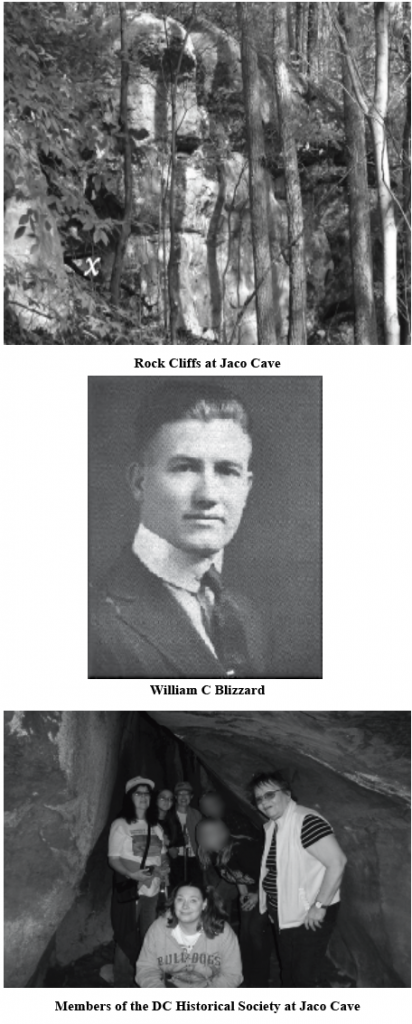

This short description of the Jaco Cave Story and related subjects of interest were written by William C Blizzard has been a hand-out offered by the D C Historical Society since the 1970s. Mr. Blizzard was a journalist, historian, & photographer born on Cabin Creek, located on the south bank of the Kanawha River in Kanawha County, WV. His extensive collection is housed at the McConnell Library Archives and Special Collections, McConnell Library in Radford, VA.

“God,” said John Brown of Osawatomie and Harpers Ferry, has given the strength of the hills to freedom; they were full of natural forts, where one man for defense will be equal to a hundred for attack; they are also full of good hiding places, where large numbers of brave men could be concealed, and baffle and elude pursuit for a long time.”

So spoke John Brown of Springfield, Mass., in 1847. He was speaking to one man only: Frederick Douglass, former slave, and legendary Negro leader. Brown was outlining to Douglass his plan to establish armed guerrilla bands in the Appalachians to strike at the slaveholders.

If Brown’s knowledge of the ethical geological intent of the Supreme Bei ng may be doubted by modern readers, his analysis of the guerrilla value of the Appalachians, and all similar prune-like formations, was full of earthly common sense. He was also describing and area where refugees from slavery might hide while fleeing north to freedom.

Brown did not convince Douglass of the wisdom of his guerrilla plan – its value as compared with risks and sacrifices involved. But in 1847, both men knew of the value of the wrinkled Appalachians as a route of the Underground Railroad, a freedom road for escaping blacks.

Prior to the Civil War, there were few main highways through the mountains of what is now West Virginia. Two of these were the Northwestern Turnpike, completed from Winchester to Parkersburg in 1838, and the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike, completed in 1847. A third, the James River and Kanawha Turnpike, had been completed from the James River to the Ohio River as early as 1800.

Although official histories are understandably silent on the subject, it is reasonable to believe that all these major turnpikes were utilized by escaping Negro slaves. Like other travelers, such escaping slaves, on any organized basis, had to have way stations for rest, food, and drink.

Such resting spots, or inns-of-desperation, had to be manned by brave, trustworthy people. Often, without doubt, they were private homes; ideally, they were places that could be easily and effectively defended.

The location of most of these way stations is doubtless lost to history. But one, near West Union, in Doddridge County, is strongly identified by legend as an Underground Railroad stop, a crude inn for runaway slaves.

This crude inn (if such it actually was) is now called Jaco Cave; it is located on Jaco Hill near West Union. The name is pronounced “Jake-O,” and was the surname of Luke Jaco, who owned the cave during the middle of the 19th century. Reference to Jaco Cave and its role in the Underground Railroad is made in the West Virginia Guide, published in 1941, but the Guide writers spelled the name “Jacko,” which is almost certainly incorrect.

Jaco Cave is located on a low hill only a few hundred feet above the old Northwestern Turnpike, now U.S. 50. In this area, the new 4-lane highway is in the same place as the old turnpike, so Jaco Cave is (the last few words in this sentence are unreadable on our copy) an archeologist. It is not an enormous shelter, but is a most excellent one, a recess about 20 feet deep enclosed on three sides.

Adjacent to this enclosed room is another stone shelter open on two ends, affording less protection than Jaco Cave proper, but still a reasonably good shelter. On the other side of Jaco Cave is a sheer, vertical sandstone face, 30 feet high or more that might also give protection against the elements.

Local legends assert that skeletons were once found in the clay floor of Jaco Cave. If so, investigators should consider the probability that they were of Indian origin.

Several years ago, a skeleton was found under cliffs bordering U.S. 119, near Peytona, in Boone County, on Drawdy Creek. Suspecting foul play, the finders notified the sheriff.

It was later discovered that the bones had belonged to an Indian (experts can tell through tooth characteristics and other features), who had probably died long before the sheriff’s grandfather was born. The bones in Jaco Cave, if such there were, might also have been aboriginal.

Residents of Doddridge County tell numerous tales of Luke Jaco, many of them unflattering. He came to West Union according to on account, about 1845, purchased the hill, cave, and other property, and set up a large inn on the Northwestern Turnpike below what is now called Jaco Cave.

Luke, according to some stories, had wild, wild ways. Wealthy guests, it was said, came to his inn and did not depart therefrom. (Such rumors were often started when an anti-slavery white man or woman had the audacity to participate in the Underground Railroad.) After the Civil War, Luke and his family moved to Missouri. Around West Union, it was reported that he had opened another inn in that state and was yet operating in the most unconventional manner.

Luke was shot and left for dead near West Union, losing an arm as a result. The shooting, according to local gossip, was simply the result of a brawl.

Yet most of the peculiar happenings that were supposed to have occurred around Luke Jaco’s inn could have been related to his clandestine Underground Railroad activity. (Many believed and continue to believe that this was the case.) That Jaco used the cave that bears his name as a haven for escaping slaves was a common story around West Union and remains to this day.

As this was strong Union territory, it is probable that many local citizens looked upon Jaco’s Underground Railroad with approval. A story in the May 1933 issue of the West Virginia Review represented that Ephraim Bee, a prominent West Union resident, aided Jaco about 1857 in his unlawful aid to escaping blacks.

This story by James Wesley McCarty is highly fictionalized in style, but the author, obviously, believed it to have a backbone of truth.

There are other interesting facts about this Doddridge County area. In the first place, John Brown of Harpers Ferry fame lived near West Union in 1840 for at least a month and possibly for almost three months.

Brown was surveying lands for Oberlin College, but he surely took time to look up unusual natural features such as Jaco Cave. He had to be familiar with this section of the Northwestern Turnpike, completed a few years earlier. He had every intention of settling permanently between West Union and Center Point, and there is indisputable historical evidence that he was sharply disappointed when his selected home site was made unavailable to him.

There can be no doubt that Brown intended to be active, from his home near West Union in the antislavery cause. In the summer of 1859, Brown, although a hunted man actively planning his Harpers Ferry raid, appeared in nearby Clarksburg to aid the free Negro woman accused of helping slaves to escape. It is tempting to infer that there was a connection between Luke Jaco and John Brown, although there is no evidence to support such a conclusion.

Jaco was not a native of the West Union area, and his name is not a common name in Appalachia. There are a few Jacos now living in and around Grafton and Morgantown, but all disclaim any knowledge of the famed Luke Jaco of West Union.

Mrs. Mabel C Ford of Moran, Kansas, now 81, wrote to the author of this article on July8, 1971:

“Grandmother was a Jaco, but her father (here again are two lines which cannot be determined.) mother at 14, two boys older and a sister younger.

“…My mother lived in the home of a great uncle for some time, or until she married my father, John Stanton Ford. The Fords were descendents of the Hanways…”

Samuel Hanway was the surveyor of Monongalia County in 1784 who owned large chunks of early Morgantown. George Washington visited Hanway’s office near Morgantown in that year and there conferred with Albert Gallatin, later Secretary of the Treasury under Thomas Jefferson about varied real estate.

The Father of His Country, anyone may see, believed that he should have free and clear deeds to as much of that country as possible. The Jacos living in Morgantown today are also probably related to Samuel Hanway.

No West Virginia Jaco of today, whatever his descent, admitted to the writer any knowledge of the Luke Jaco of yesteryear. The name, according to present-day Jacos is of French origin.

When Luke Jaco left West Union after the Civil War, he sold his property, including the cave, to Chapman J Stuart. If not actually a friend of Jaco, Stuart knew the man well. And who was Chapman J Stuart? He was the man who named West Virginia.

An attorney who had studied at the old Monongalia Academy in Morgantown and the Western University of Pennsylvania (now the University of Pittsburgh), Stuart was a prominent organizer, after the Civil War of the new state of West Virginia. He was a member of the Wheeling Convention of 1861 that repudiated the Ordinance of Secession and organized the Restored Government. He was chairman of the boundary committee.

He was elected to the state senate and was with the Restored Government at Wheeling until the new state of West Virginia was formed. He was, in 1861, a member of the convention that framed the West Virginia constitution and called that convention to order. He was a member of the first nominating convention held in the new state and also called it to order.

Several names were suggested for the severed western section of the Old Dominion, including “New Virginia”, and “Allegheny.” Stuart suggested “West Virginia” to the conference committee. His motion was defeated at the time, but was later adopted by the constitutional convention, so Stuart named the state of which he was a founding father.

What of Ephraim Bee, in one account connected with Luke Jaco in Underground Railroad activity? Bee was the West Union postmaster for many years as well as the village blacksmith. He was a member of the first West Virginia legislature, and served two succeeding terms.

Having little formal education, Bee was unable, like his neighbor, Chapman Stuart, to name West Virginia, but he did what was possible. His fifth daughter by his second marriage was born on the day President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill that created the Mountain State.

What did Ephraim Bee name the daughter? What else? He named her West Virginia.

It could have been worst. There were lots of Indian names in favor at that time, and the new state could have been called Youghiogheny, or Conshonocken, or Daguscahonda.

In which case the fifth daughter of Ephraim Bee, when she reached 21, might have caused her father to take refuge in that sanctuary of freedom, Jaco Cave. General sympathies, in that case, would likely have been with the pursuer rather than the pursued.

(This copy of the Legend of Jaco Cave was donated to the Doddridge County Historical Society by Jacqueline Wetzel and Mary Franklin.)

God Bless and Stay Well

Patricia Richards Harris